'I never had a regular girlfriend at school... but in Duran Duran I only had to wink in a girl's direction': John Taylor's shamelessly honest inside story of THE pop phenomenon of the 1980s

By John Taylor

PUBLISHED: 16:00 EST, 1 September 2012 | UPDATED: 16:00 EST, 1 September 2012

It’s a Monday night at the Brighton Dome, 1981, two weeks before our third single, Girls On Film, is due out. It’s a week after my 21st birthday. The lights go down and our curtain-raiser starts. But something strange is happening.

None of us can hear the music. Only the sound of an audience. Getting louder. Larger. Chanting. Screaming. Then out on to the stage we go. A frisson of fear. And the curtain rises.

The power of our instruments, amplified by stacks that reach to the roof, is no match for the overwhelming force of teenage sexual energy that comes surging at us from the auditorium. I can feel it take control of my arms, my legs, my fingers. It is unrelenting, waves of it crashing onstage.

There is no way we can be heard, but that doesn’t matter. No one is listening to us anyway. Seats are smashed. Clothes torn. Stretcher cases. Breakdowns. The frenzy is contagious. We have become idols, icons. Subjects of worship.

There was a shortage of affordable homes in the Fifties, so Mum and Dad’s brand new house in Hollywood, south Birmingham, was perfect. It was a two-up, two-down, with a pebbledash relief below the upstairs bow windows.

The living room was where we would eat, watch television, sit, do just about everything. The other downstairs room, the ‘front room’, was where the alcohol was stored.

Number 34 Simon Road had its own garage, where my father would spend weekends tinkering with his car. There was a small garden at the front and a slightly larger one at the back. In June 1960, Mum gave birth to me at Sorrento Maternity Hospital in Solihull. My parents named me Nigel. My second name was John.

I first met Nick Bates in the winter of 1973 when I was 13 and he was 11. Nick had already been to a couple of concerts – yes, this boy was advanced – Gary Glitter and Slade. But Bowie was king at that time, and deservedly so.

New Romantic: John was inspired by the clothes, hairstyles and make-up of Britain's glam-rock era

Nick and I both wore chiffon without needing much encouragement, and we both loved the clothes, the hairstyles and the make-up of Britain’s glam-rock era. Bryan Ferry’s sartorial direction was having its effect: boys were going through their dad’s wardrobes to find the baggy double-breasted suits such as those Bogie wore in Casablanca. Dad’s fitted me perfectly.

But then there was the transsexual glam aspect, and we found ourselves mixing it up with ladies’ blouses. At British Home Stores, in the city centre, there was a huge floor filled with two-piece ladies’ suits. Some of those jackets were divine, and fitted both Nick and me. Throw in a little chiffon, maybe an animal-print scarf from Chelsea Girl, and you were away.

‘You’re not going out dressed like that?’ our parents would cry.

‘Don’t you worry about it, Father,’ Nick would tell his dad as I applied a little lip gloss in their bathroom.

‘Oh, leave them alone, Roger,’ his mum, Sylvia, would say. ‘They’re just having fun.’

After telling a sceptical school careers officer that I wanted to be a ‘pop star’, I enrolled at Birmingham Polytechnic’s College of Art and Design for a 12-month foundation course.

For me, going to art school was inspired more by musical heroes: John Lennon, Keith Richards, Bryan Ferry. I hoped to hook up with other like-minded souls, just as they had.

Seeing The Human League for the first time was a turning point. Nick and I saw them supporting Siouxsie and the Banshees at the Mayfair Ballroom in the Bullring shopping centre and watched in amazed silence. They had no drummer. No guitars. They had three synthesisers and a drum machine instead.

So Nick’s mum, Sylvia, made a £200 investment: the first Wasp synthesizer to arrive in Birmingham, purchased at Woodroffe’s music store. We also bought a Kay rhythm box for £15. It had presets such as ‘mambo’, ‘foxtrot’, ‘slow rock’ and ‘waltz’.

With Nick controlling the keys, an art-school friend singing and on bass, and me on guitar, we made our first recordings on cassette in the space above Nick’s mum’s toy shop. The resulting ‘album’ was called Dusk And Dawn.

I was proud of this first attempt and decided to offer it as my year-end project at college. Each student was allotted a space in the main hall to display the fruits of their labour. I covered my wall with a shiny black plastic dustbin liner and placed the solitary tape on the table in front of it.

There was a certain amount of chutzpah required as the college faculty circled my presentation. Professor Grundy picks up the cassette, handles it gingerly.

I thought I was a Master of the Universe. But I was just a rat trapped in a gilded cage

Grundy: ‘And what is this exactly?’

Me: ‘It’s what I’ve been doing for the last six months.’

Grundy: ‘And what are you hoping to do with it?’

Me: ‘Get a record deal.’

Grundy: ‘It doesn’t really relate to your course work though, does it?’

Me: ‘Why should it? This is art because I say it is.’

Grundy: ‘Well, I am glad you’ve learned something in your time here, Nigel.’

That was my last day in academia.

On the cassette liner, I appear under my birth name, Nigel. Shortly after, I decided that a pop star named John Taylor sounded better than Nigel Taylor. I’d been sick of Nigel for years. It had been the nerd-name of choice for so much satire. In Monty Python’s Upper Class Twit Of The Year TV sketch, the biggest twit of them all was called Nigel. Nigel had to go. But John – Johnny – was a rocker.

It was more than just taking a stage name. I didn’t want to be called Nigel by anybody: the band, my friends, my family. It would take Mum years to get with the John plan.

Nick and I were as one on this line of thinking. It was his surname, Bates, that didn’t fit the picture. Rhodes seemed to have the right blend of high and low culture, drawing as it did from The Clash’s manager, Bernie, and fashion’s high priestess, Zandra.

Simon Le Bon was a tall, well-spoken drama student from nearby Birmingham University. He came to see us rehearsing clutching a blue notebook of lyrics and ideas for songs and listened as we played, making notes. Then he stood up, all 6ft 2in of him, sauntered over to the mic, book open, and began to sing.

I wrote in my diary that night: ‘Finally the front man! The star is here!’

With Simon as our vocalist, the line-up was complete: Andy Taylor on guitar, Roger Taylor on drums, Nick Rhodes on keyboards. And me, on bass.

We booked a date downstairs among the neon lights and MirroFlex- covered walls of Birmingham’s Rum Runner nightclub. Wednesday, July 16, 1980 – our first show.

Simon addressed the crowd: ‘We’re Duran Duran, and we want to be the band to dance to when the bomb drops. This is Late Bar. We wrote it for you to dance to.’ Roger counted it off: ‘1-2-3-4.’ And in we went.

Looking at photos from that first gig, I am struck by how eclectic and outrageous the scene was. Everyone had dyed, styled or shaved their hair. Most were wearing make-up. Pretty standard for a Tuesday night in 1980.

Tours and our first album soon followed. And the fan mail. We would gather in the Rum Runner in the afternoon and sit there doing more homework than we had ever done at school, signing photos and writing replies to letters.

The fans would do some pretty crazy things over the years, but my favourite has to be the girl in Atlanta who was at a press conference. I had a cold, and was sniffling into tissues, throwing them into a bin under the table.

Next time we were in the city the girl called out to me at another public appearance: ‘I was the girl who got your cold . . . After you left the press conference last year I stole your used tissues. I wanted to get your cold.’

I had been a nerd at school, never had a regular girlfriend. Now, I had only to wink in a girl’s direction in a hotel lobby, backstage or at a record company party, and have company until the morning.

So what’s the problem, you might ask? Well, the trouble is – and I didn’t figure this out until I was almost 40 – that there is something about an intimate encounter of that nature with someone you barely know that jars against the spirit. You want it, but it doesn’t feel quite right. And when you start doing it night after night, week in, week out, your ideas about love and sex begin to get distorted.

On tour, I learned that girls liked taking drugs with me. My horror of lonely hotel rooms meant I would go to any lengths to avoid sleeping in them alone. I was a pin-up on thousands of bedroom walls, but fear of loneliness was turning me into a cokehead.

Jumping into bed like porn-star Johnny is not as easy as you might imagine. You feel awkward. Or at least I did. Maybe it was some residue of Catholic guilt? Plain old common decency? The drugs took away all those doubts.

Of absolute necessity for any touring musician is the itinerary. It usually comes on the last day of rehearsal. It lists the principals, the inner circle and the crew, the numbers to call if in trouble, then a page-by-page account of the destinations.

In the left-hand corner of each page of the American itinerary there was a number, usually 18, 21 or 20. It was months before I was let in on the secret: the numbers referred to the legal age for sexual intercourse in that particular state.

I assumed that the girl-pulling powers I was enjoying on the road would continue when I was at home. This turned out not to be the case. There’s something about being in a touring band that acts as an aphrodisiac. Maybe it’s being in a city for just 24 hours; the girls who want you have to act fast.

Back in Britain, my agent Rob and I struck out most nights. We would start out the evening reeking of aftershave, hairspray and optimism, but our ‘failures to launch’ became something of a running gag. Years later, a prominent club owner said: ‘We all thought you guys were gay.’

I had become used to travelling at a stratospheric pace, and I never wanted it to end. Sitting in the living room of my Knightsbridge house and ‘watching the telly’ or ‘having friends over for dinner’ was too banal. Plus, there was a 24-hour fan encampment outside the house, squealing and snapping their cameras whatever time I got home.

The first thing I would hear when I woke would be the chatter of the fans outside. I would crawl to the window and peek through the curtains. If they didn’t know I was awake yet, I might at least be able to run a bath and get dressed without having to hear ‘Save a Prayer for me now, John’ drifting up from the street.

The madness was always a micron below the surface, kept at bay by our shared sense of humour. Only Andy would make reference now and again to the sourness that he felt was creeping in, that we were rats in a gilded cage, subject to the whims of the managers, agents and corporate brand consultants. We were sponsored by Coca-Cola.

I crossed a line when I started getting high on stage. I had always remained sober for the duration of the show, as I wanted to give my best. But now I couldn’t wait for the performances to end. I wanted to take back control of my life, and getting high felt like that.

At the end of the main set, I headed for the backstage bathrooms to snort up $100 worth of coke through a rolled-up $100 bill. It felt so ‘big-time’, so ‘rock star’.

And I would tell myself it gave me the capacity to absorb all the incredible energy that the audience was hurling at me. I was a Master of the Universe. Or so it seemed. Once we were done with our encores, I was really ready to let rip.

Alcohol and drugs were beginning to take control, not just of decisions and choices I made, but also with whom I hung out. One of the worst effects of this was that I didn’t want to be around Nick any more, my oldest friend, simply because he never supported my using. Nick was just not a drug user.

Back in the studio in 1983, we were burning out everyone around us. When it was announced one morning that changes had been made to one of the arrangements for Seven And The Ragged Tiger and I was wanted in the studio, I freaked out. I was in the bathroom shaving. In a moment of overreaction, I picked up a heavy glass and threw it at the shower door, smashing it into a million pieces. ‘That song was finished! I’m finished! I’m done!’

It was the beginning of a rift that would deepen over the next two years: Andy and I on one side, Simon, Nick and our managers on the other. Roger did a balancing act between us.

I KNOW WHO YOU ARE, SAID MY DRIVING EXAMINER

I had finally made the time to take my driving test. I had been sure I would be driving at 19 or 20, tops, but Duran had taken over.

In the way that the British have of reminding one not to get above one’s station, the grey-suited examiner took a moment before the test began to address me.

‘Now, Mr Taylor, I want you to know that I know who you are. In fact, my daughter has pictures of you all over her bedroom wall.

'But this will not influence me in any way. I hope you understand that. Now, pull away smoothly in your own time and follow the road ahead.’

I passed.

The following year, I was looking forward to taking some time out from my Duran persona. Mum and Dad were so excited to see me, of course, but what had really blown their minds, and what they wanted to show me the moment I stepped out of the car, were four giant sacks of mail that the Post Office had delivered on Christmas Eve.

Fan mail. Love letters. Pleading. Begging. Who knew? Where could I begin?

I was struck that 10,000 people wanted to have a relationship with me and I could barely have a relationship with myself.

And these two guardians of the mail sacks? They looked very like Mum and Dad. But they sounded like two fans who had somehow found their way into the house and inhabited my parents’ shells. Invasion of the Parent Snatchers!

I couldn’t take it. I emptied all the sacks in a rageful frenzy, dumping the contents on the floor, scattering the letters and cards all over the garage, frothing at the mouth, tearing up the envelopes unopened. My parents watched the rampage, their mouths agape.

‘Don’t you get it, you two? I don’t f*****g care about any of this!’

After a rather fretful turkey dinner, I drove off back to London and booked a plane ticket to New York for the next day. Hotel. Room service. Cocktail. A line or two. That’s better.

Alone in the small hours one morning, I thought I needed spiritual salvation. And as the dawn rose, it was St Jude’s, the Catholic church of my childhood that filled my imagination. I just had to write a chorale for Father Cassidy, our parish priest!

On the table, among the unfinished drinks and overflowing ashtrays, were scatterings of powdery cocaine crumbles. It was a circular chain-link fence; cigarettes, drink, drugs, each causing me to crave the others. Once I had started on the one, the system clamped me in its jaws. One line and I was gone, off to the races. I was no longer managing the chaos.

What was left of last night’s supply waited in its crisply folded white envelope. I called my mum.

‘Hello, John, where are you?’

‘New York, Mum, at the apartment.’

‘That’s nice. Your father’s gone to get the paper.’

‘Mum, I need Father Cassidy’s number. I want to write a piece of music for the church.’

‘Are you sure?’

She gave it to me. I had just enough coke left to get me through this next call. Father Cassidy didn’t pick up, thanks be to God.

On Christmas Eve 1991, I married Amanda de Cadenet at Chelsea Register Office on the Kings Road. Amanda had blonde hair and blue eyes, and looked like an angel.

A few months after we met, she got a job presenting a late-night music and culture show called The Word. She was a natural networker.

Her career plans seemed to my jaded eye to involve going to a lot of parties or having intimate dinners for two with movie stars at their Mulholland lairs. I didn’t feel good about that. I was feeling my age.

I found myself resenting those who looked, from the outside, to have a regular family life. I was angry because I just couldn’t seem to make that side of my life work. Simon had been diligent about his family. His three daughters were thriving. His family loved spending time in each other’s company.

Yes, Amanda and I had our own daughter, Atlanta, but we could not settle down. Once the novelty of playing house had worn off, we reverted to our old ways.

Amanda was a decade younger than me, and she was just getting into the big schmooze, the million tiny seductions required to make her famous. When I came home, I wanted to chill, and she would be off out. We were not on the same planet.

I went to rehab in America, not with the intention of making my marriage work. I had already written it off. I imagined the gap between Amanda and I to be too great and our problems insurmountable. I was too used to wanting an easy way of dealing with things, and if they couldn’t be dealt with easily, then I wouldn’t deal with them at all. So my marriage to Amanda never got the benefit of my sobriety, although our separation did.

It’s April 2011 and Duran Duran are back on tour – Roger, Nick, Simon and me.

We have come a long way together and a lot has changed in the past 30 years. Cell phones. Computers. SUVs. Nose-hair trimmers. Supplements. In-room humidifiers. Steam rooms, saunas and gyms. Pre-show massage. Twitter, Spotify and Amazon.

Touring with 3,000 songs in my pocket and 30 books on an iPad. Therapy by Skype. Great coffee everywhere. Another difference is out there, where there are just as many men as women in the audience tonight.

A perfect breeze causes my Buddha scarf to flutter. All the signs are good. We walk together up the ramp, Nick first, in a black net snood borrowed from Lady Gaga.

He touches the Andromeda synthesiser, from which issues a sample of the exact sound he used to begin our first single, Planet Earth, all those years before. My heart is pounding. There is no better time than this.

Roger’s drums kick in. An eight-bar count and I’m in with him, the galloping groove that started it all for me.

Thirty thousand California kids, eyes and teeth smiling, cameras and cell phones popping, a million tiny seductions all at once.

© John Taylor 2012. In The Pleasure Groove by John Taylor is published by Sphere, priced £18.99. To order your copy at the special price of £16.99 with free p&p, please call the Review Bookstore on 0843 382 1111 or visit mailshop.co.uk/books

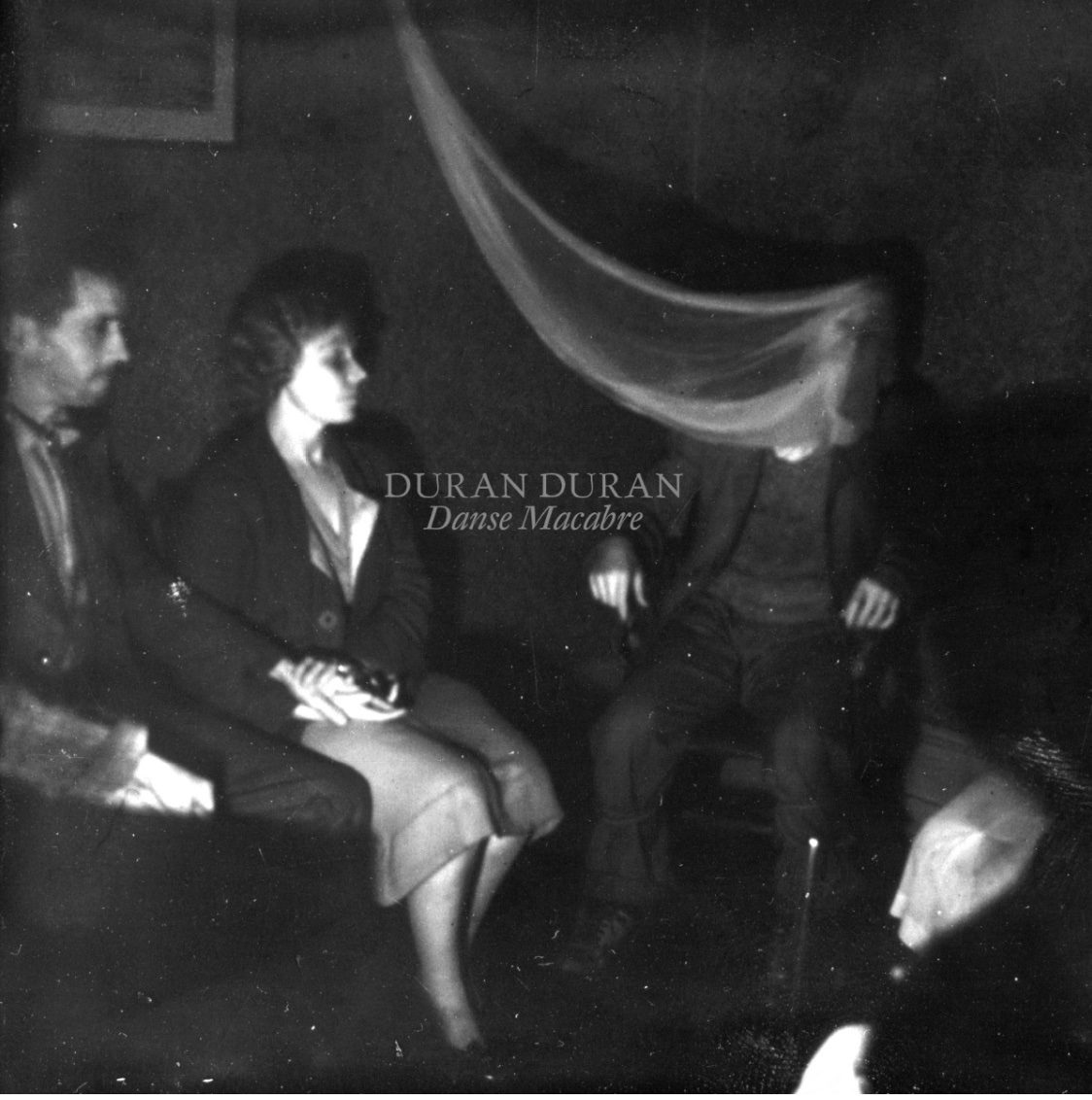

Read more & see photos here